Colorado State University hurricane researchers predict an “extremely active” Atlantic hurricane season in their initial 2024 forecast. The team cites record-warm tropical and eastern subtropical Atlantic sea surface temperatures as a primary factor for their prediction of 11 hurricanes this year.

Led by senior research scientist and Triple-I non-resident scholar Phil Klotzbach, Ph.D, the CSU Tropical Meteorology Project forecasts 23 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and five major hurricanes during the 2024 season, which starts on June 1 and continues through Nov. 30. A typical Atlantic season has 14 named storms, seven hurricanes, and three major hurricanes.

The 2023 season produced 20 named storms and seven hurricanes. Three reached “major hurricane” intensity. Major hurricanes are defined as those with wind speeds reaching Category 3, 4 or 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

“We anticipate a well above-average probability for major hurricanes making landfall along the continental United States coastline and in the Caribbean this season,” Klotzbach said. “Current El Niño conditions are likely to transition to La Niña conditions this summer/fall, leading to hurricane-favorable wind-shear conditions. Sea surface temperatures in the eastern and central Atlantic are currently at record-warm levels and are anticipated to remain well above average for the upcoming hurricane season. A warmer-than-normal tropical Atlantic provides a more conducive dynamic and thermodynamic environment for hurricane formation and intensification.”

One hurricane and two tropical storms made continental U.S. landfalls last year. Category 3 Hurricane Idalia struck Florida’s Big Bend region near Keaton Beach on Aug. 30 with wind speeds of 115 mph. It was the third hurricane, and second major hurricane, to make a Florida landfall over the past two seasons. Idalia caused storm surge inundation of 7 to 12 feet and widespread flooding in Florida and throughout the Southeast.

“The widespread damage incurred from Idalia last year highlighted the importance of being financially protected from catastrophic losses – and that includes having adequate levels of property insurance and flood coverage,” said Triple-I CEO Sean Kevelighan. “Beyond Florida, we saw significant impacts from Idalia in southern Georgia and the Carolinas. All it takes is one storm to make it an active season for you and your family, so it is time to prepare as the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season’s start nears.”

With this forecast in mind, now is ideal time for homeowners and business owners to review their policies with an insurance professional to ensure they have the right amount and types of coverage. That includes exploring whether they need flood coverage, which is not part of a standard homeowners, condo, renters or business insurance policy.

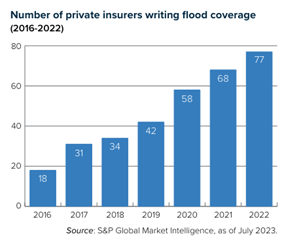

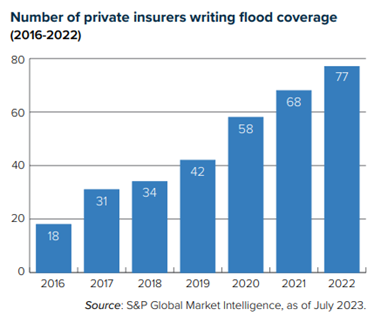

Flood policies are offered through FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and dozens of private insurers.

Homeowners also can make their residences more resilient to windstorms and torrential rain by installing roof tie-downs and a good drainage system. Installation of a wind-rated garage door and storm shutters also boost a home’s resilience to a hurricane’s damaging winds and may generate savings on a homeowner’s insurance premium.

Private-passenger vehicles damaged or destroyed by either wind or flooding are covered under the optional comprehensive portion of an auto insurance policy.

Learn More:

Triple-I “State of the Risk” Issues Brief: Hurricanes

Triple-I “State of the Risk” Issues Brief: Flood

FEMA Highlights Role of Modern Roofs in Preventing Hurricane Damage

Hurricanes Drive Louisiana Insured Losses, Insurer Insolvencies

INFOGRAPHICS

What are Hurricane Deductibles?

How to Prepare for Hurricane Season