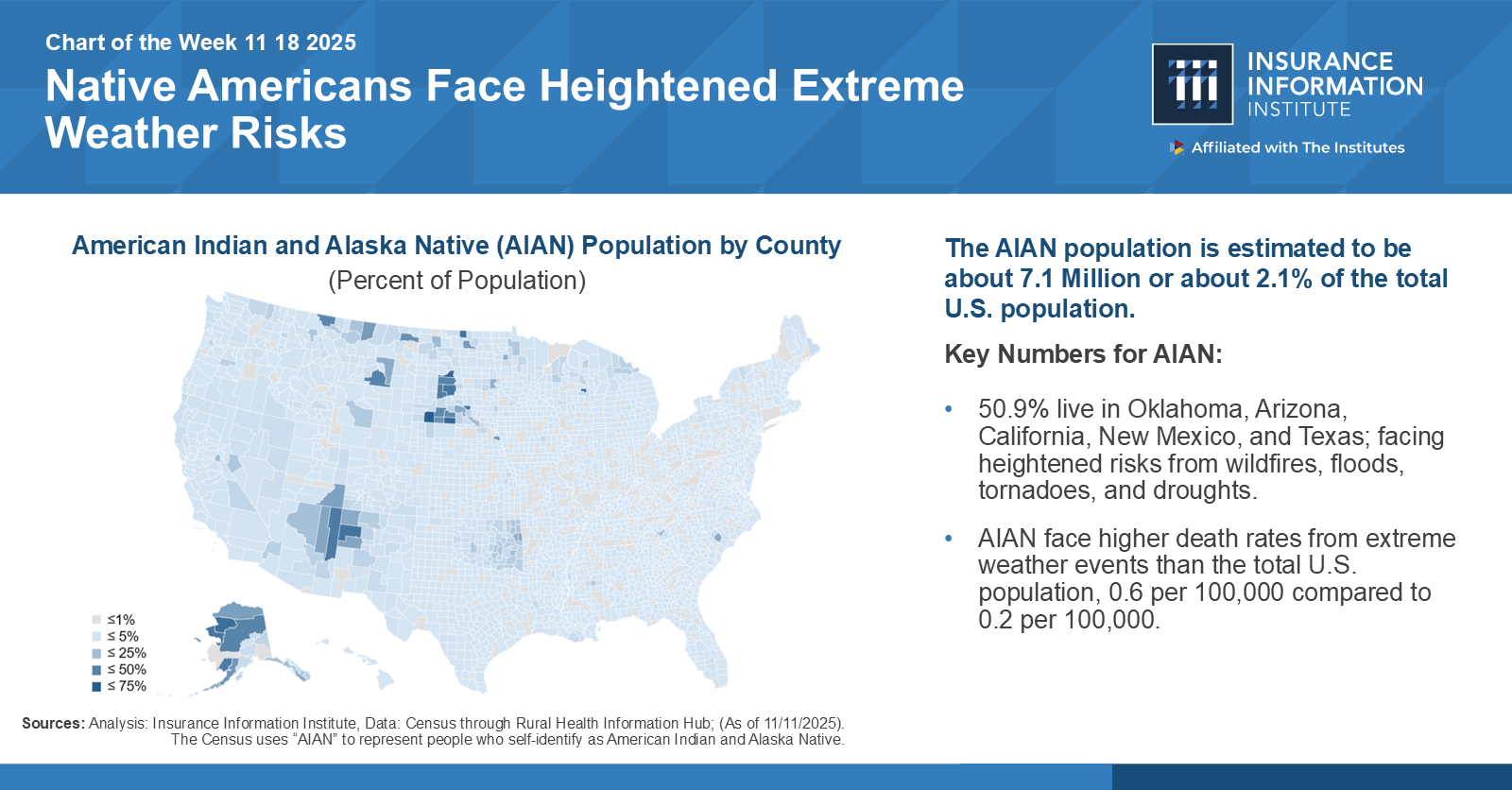

As part of an ongoing discussion on the link between the housing and insurance markets, the Insurance Information Institute (Triple-I) released a Chart of the Week (COTW) that provides a snapshot of climate risk concerns for American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) population.

The provided estimate for the number of Native Americans in the U.S. is 7.1 million – about 2.1 percent of the total population. As much as 95 percent of the general U.S. population lives in a county that has experienced a natural disaster since 2011. However, this COTW says at least 50.9 percent of Native Americans live in states facing heightened risks from wildfires, floods, tornadoes, and droughts. The chart also reveals that Indigenous people in the U.S. face higher death rates from extreme weather events than the total national population, at 0.6 per 100,000 compared to 0.2 per 100,000.

Native communities are situated on the front line of climate risk.

As insurance is designed to help policyholders and their communities recover from insurable events, coverage availability and affordability can contribute to resilience. However, states that are home to at least half of the U.S. Native American population rank high on the Insurance Research Council (IRC) report, Homeowners Insurance Expenditures as a Percent of Median Household Income – Oklahoma (4th), Arizona (5th), Texas, (6th), New Mexico (14th), California (25th) – indicating comparatively less coverage affordability in those states. While availability and affordability can ultimately be driven by a mix of key underlying cost drivers, climate risk and home-ownership challenges can play a crucial role in access for many Native American homeowners.

Extreme weather events, such as hurricanes and typhoons, have shaped the way colonization of North America unfolded, beginning in the early centuries of European contact. For thousands of years prior, Native Americans had thrived in their homelands by taking measures to survive long-term severe weather, such as seasonally migrating away from flood-prone areas or building nature-based infrastructure as needed. Colonial expansion, in which Indigenous people lost nearly 99 percent of their historical land base over time, decimated Indigenous populations and pushed survivors into high-severe-weather-risk areas or lands, in many cases previously unknown to their respective tribal groups.

As a result of centuries of these forced removal policies and government-directed or sanctioned land dispossession, present-day Native American lands “are also generally far from historical lands, averaging a distance of roughly 150 miles” and are often in inherently more climate risk-prone areas today – i.e., low-lying, exposed, less habitable due to drought, etc. Living today on the front lines of climate risk across the U.S. means frequently experiencing acute effects, such as thawing permafrost, rising sea levels, increased flooding, stronger storms, erosion, and shifting ecosystems.

For instance, a 2024 study indicates that Oklahoma, home to 39 federally recognized tribal nations, “faces climate and demographic changes that disproportionately put many Native Americans at risk. The heavy rainfall, 2-year floods, and flash floods are all projected to have increased risks by 501.1 percent, 632.6 percent, and 296.4 percent, respectively.”

In a village in western Alaska, where permafrost is thawing, buildings (including a preschool) are shifting, water intrusion is increasing, and relocation is becoming a real threat. Recently, nearly 50 Alaska Native communities experienced “towering wind speeds, record storm surge, and widespread flooding”, resulting in at least one death and the displacement of 1,500 people. Initial estimates have reported that the storm decimated 90 percent of homes in the coastal village of Kipnuk and 35 percent in Kwigillingok, “which has also experienced toxic chemicals spilling into its freshwater supply.”

Climate risk can threaten lives and property, of course, but also regional economies, one of the key ingredients in building capacity for resilience. For example, a study of climate-driven economic challenges posed to Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in the U.S., shows that “drought has a larger impact on cattle production than hay production, resulting in total economic losses of $8.2 million and $0.4 million for the cattle and hay sectors, respectively.” Without robust regional economies, infrastructure, or policy support, Native American homeowners and their communities may struggle to adapt or relocate effectively.

Homeownership costs may contribute to the protection gap.

Native American homeowners are more likely to lack coverage if they:

- Are homeowners living in New Mexico and certain rural areas of Texas

- have manufactured homes, or

- own inherited homes.

Data collected through the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) reveals that Native Americans, on average, pay more to finance their homes – in some contexts up to two times more. While that disparity can be attributed to several factors, one major driver is the loan type that appears to be more common among Native borrowers, home-only loans. “Nearly 40 percent of loans to Native American borrowers on reservations were for manufactured homes, compared to 3 percent of loans to White borrowers”. Further, about 8 out of 10 manufactured-home loans were home-only loans.

Home-only loans, a financing tool used for movable personal property in which the lender retains ownership of the property until the borrower fully pays the loan, can make financial sense in some instances. Nonetheless, borrowers typically pay higher interest rates and have fewer consumer protections, such as federal guarantees, than regular mortgages. The pressure of these circumstances may compel the homeowners to carry insufficient coverage, or, when they pay off the loan, none at all.

Federal funding freezes can impede resilience.

Data from the National Congress of American Indians show that “U.S. citizens receive, on average, about $26 per person, per year, from the federal government, while tribal citizens receive approximately $3 per person, per year.” Recent federal disinvestment in 2025 from crucial risk prevention and management programs and other supportive infrastructure – including public radio stations which can be used for advance severe weather warnings and coordination of disaster recovery efforts – has exacerbated the burden from longstanding disparities. This decrease in support can also heighten the need for insurance coverage and closing the protection gap.

Amy Cole-Smith, Executive Director for BIIC/ Director of Diversity at The Institutes says, “the numbers are clear: Native Americans face higher exposure to extreme weather, higher insurance burdens, and higher rates of being uninsured. These factors reflect not just climate trends but historical inequities that continue to shape outcomes today. Strengthening coverage access is essential to protecting lives, homes, and cultural continuity.”

As Smith has often expressed, one way the industry can start closing the protection gap is “by having people at the table who understand the lived experiences behind the numbers.”

Triple-I works to advance the conversation around crucial issues in the insurance industry. We invite you to follow our blog to learn more about trends in insurance affordability and availability across the property/casualty market.