By Sean Kevelighan, Triple-I CEO

Legislation proposed by U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.) to create a federal “catastrophe reinsurance program” raises several concerns that warrant scrutiny and discussion – starting with the question: Does what’s being proposed even qualify as insurance?

If enacted into law, the bill would establish a “catastrophic property loss reinsurance program…to provide reinsurance for qualifying primary insurance companies.” To qualify, insurers would have to offer:

- An all-perils property insurance policy for residential and commercial property, and

- A loss-prevention partnership with the policyholder to encourage investments and activities that reduce insured and economic losses from a catastrophe peril.

The proposed program would phase in coverage requirements peril by peril over several years and discontinue FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). It would set coverage thresholds and dictate rating factors based on input from a board in which the insurance industry is only nominally represented.

And nowhere in the 22-page proposal do any of the following words or phrases appear:

- “Actuarial soundness”;

- “Risk-based pricing”;

- “Reserves”; or

- “Policyholder surplus”.

Actuarially sound risk-based pricing and the need to maintain adequate reserves and policyholder surplus to ensure financial strength and claims-paying ability are the bedrock of any insurance program worthy of the name – not technical fine print to be worked out down the road while existing mechanisms are being dismantled and market forces distorted through government involvement.

Insurance is a complicated discipline, and prior federal attempts at providing coverage have struggled to balance their goal of increasing availability and reducing premiums against the need to base underwriting and pricing on actuarially sound principles to ensure sufficient reserves for paying claims.

Actuarially sound risk-based pricing and the need to maintain adequate reserves and policyholder surplus…are the bedrock of any insurance program worthy of the name – not technical fine print to be worked out down the road…

Sean Kevelighan, CEO, Triple-I

Learn from history

NFIP is a strong case in point. Created in 1968 to protect property owners for a peril that most private insurers were reluctant to cover, NFIP’s “one-size-fits-all” approach to underwriting and pricing has led to the program now owing more than $20 billion to the U.S. Treasury because it lacked the reserves to fully pay claims after major events like Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy. It also often led to lower-risk property owners unfairly subsidizing coverage for higher-risk properties.

Having thus learned the importance of risk-based pricing, NFIP has changed its underwriting and pricing methodology. The new approach – Risk Rating 2.0, announced in 2019 and fully implemented as of April 1, 2023 – more equitably distributes premiums based on home value and individual properties’ flood risk. As a result, premiums of previously subsidized policyholders – particularly in coastal areas with higher values – have risen, leading to outcries from many higher-risk owners who have seen their subsidies reduced.

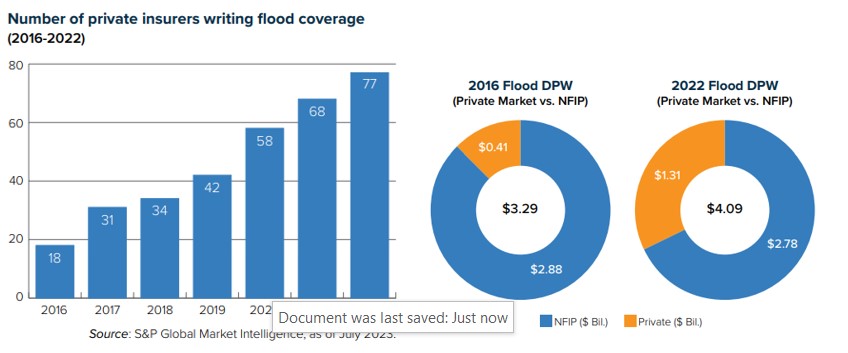

In addition to leading to fairer pricing, Risk Rating 2.0 – by reducing market distortions – increases incentives for private insurers to get involved. For a long time, private insurers considered flood an untouchable peril, but improved data modeling and analytical tools have increased their comfort writing this business. As the charts below show, private insurers have been playing a steadily increasing role in recent years, covering a larger percentage of a growing risk pool.

Over time, this trend should lead to greater availability and affordability of flood insurance coverage.

Rather than incorporating the lessons generated by NFIP’s experience with a single peril, Rep. Schiff’s proposal would discontinue the reformed flood insurance program while adding a new layer of complexity to coverage across all perils and casting into question the future of various state insurance programs and residual market mechanisms currently in place.

Time-tested principles

Any attempt by the federal government to address insurance availability and affordability concerns must be made with an understanding of how insurance works – from pricing and underwriting to reserving and claim settlement. For example, the Schiff bill proposes piloting an all-perils policy with a term of five years. There are good reasons for property/casualty policies to be written with a one-year term. Specifically, the conditions that affect claims costs can change quickly, and insurers – as referenced above – must set aside sufficient reserves to be able to pay all legitimate claims. If they cannot revisit pricing annually, the financial results could be disastrous.

“Who would have thought in 2019 that replacement costs would increase 55 percent within three years?” asked Dale Porfilio, Triple-I’s chief insurance officer. Supply-chain disruptions related to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine contributed to just such a replacement-cost spike. “Requiring five-year terms for policies would have led to a massive drain on policyholder surplus.”

Policyholder surplus is the financial cushion representing the difference between an insurer’s assets and its liabilities.

In announcing his proposed legislation, Rep. Schiff said it is intended to “insulate consumers from unrestrained cost increases by offering insurers a transparent, fairly priced public reinsurance alternative for the worst climate-driven catastrophes.”

This language ignores the fact that, under state-by-state regulation, premium rate increases are anything but “unrestrained” and ratemaking is based on actuarially sound principles that are transparent and fair. Property/casualty insurance already is one of the most heavily regulated industries in the United States.

Consumers deserve real solutions

Policyholders have legitimate concerns about affordability and, in some cases, availability of insurance. These concerns can create pressure for political leaders at both the state and federal levels to advance measures that are perceived as promising to help. Unfortunately, many recent proposals begin by mischaracterizing current trends as an “insurance crisis,” as opposed to what they really represent: A risk crisis.

Insurance premium rates tend to move in line with the frequency and severity of the perils they cover. They also are affected by factors like fraud and litigation abuse; climate, population, and development trends; and global economics and geopolitics. That is why insurers hire actuaries and data scientists and employ cutting-edge modeling technology to ensure that insurance pricing is actuarially sound, fair, and compliant with regulatory requirements in all states in which they do business.

That is how insurers keep lower-risk policyholders from unfairly subsidizing higher-risk ones.

To its credit, the federal government is working to reduce climate-related risks and investing in resilience through programs like Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZ) and FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law contains substantial funding to promote climate resilience. These are worthy endeavors aimed at addressing risks that drive up insurance costs.

But history has shown that direct government involvement in the underwriting and pricing of insurance products tends not to end well. Any plan that would attempt to micromanage insurers’ coverage of all perils through a lens that ignores time-tested, actuarially sound risk-based pricing principles raises a host of red flags that must be discussed and addressed before such a plan is allowed to become law.

Learn More:

It’s Not an “Insurance Crisis” — It’s a Risk Crisis

Miami-Dade, Fla., Sees Flood Insurance Rate Cuts, Thanks to Resilience Investment

Illinois Bill Highlights Need for Education on Risk-Based Pricing of Insurance

Education Can Overcome Doubts on Credit-Based Insurance Scores, IRC Survey Suggests

Matching Price to Peril Helps Keep Insurance Available and Affordable

Policyholder Surplus Matters: Here’s Why

Triple-I Issues Brief: Proposition 103 and California’s Risk Crisis

Triple-I Issues Brief: Risk-based Pricing of Insurance

Triple-I Issues Brief: How Inflation Affects P/C Insurance Pricing – and How It Doesn’t