Homeowners insurance premium growth in Florida has slowed since the state implemented legal system abuse reforms in 2022, according to a Triple-I analysis.

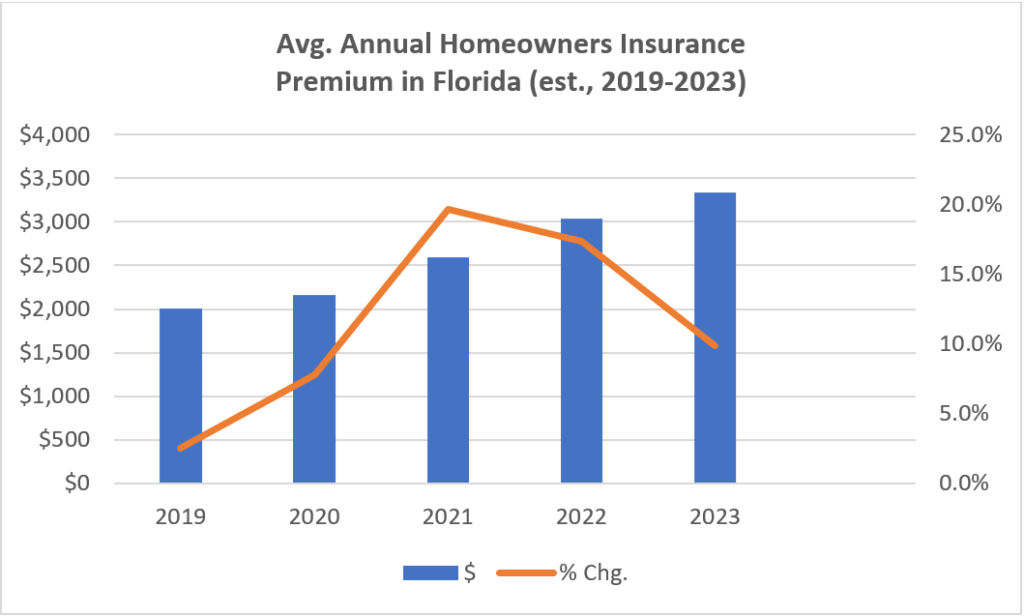

As shown in the chart below, average annual premiums climbed sharply after 2020. This was due in part to inflation spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine as well as longtime challenges in the state with claim fraud and legal system abuse.

Source: Triple-I analysis of NAIC and OIR data

According to the state’s Office of Insurance Regulation (OIR), Florida accounted for nearly 71% of the nation’s homeowners claim-related litigation, despite representing only 15% of homeowners claims in 2022, the year Category 4 Hurricane Ian struck the state. In that same year, and prior to Ian making landfall in the state as a first major hurricane since 2018’s Hurricane Michael, six insurers declared insolvency. Hurricane Ian became the second largest on record by insured losses, in large part because of the extraordinary litigation costs estimated to result in Florida in the aftermath.

The Florida Legislature responded to the growing crisis by passing several pieces of insurance reform, primarily tackling problems with assignment of benefits (AOB), bad-faith claims, and excessive fees. For example, the new laws eliminated one-way attorney fees in property insurance litigation, forbid using appraisal awards to file a bad-faith lawsuit, and prohibited third parties from taking AOBs for any property claims. The legislation also ensures transparency and efficiency in the claims process and encourages more efficient, less costly alternatives to litigation.

A surge in litigation

Litigation spiked when backlogged courts reopened following the pandemic, then again when the reforms were passed in 2022 and 2023, as plaintiffs’ attorneys raced to file suits ahead of implementation of the legislation.

This increase in litigation, combined with persistently strong inflation, contributed to increased loss costs and premium increases. In 2022, average homeowners premium rates rose more than 17 percent, to $3,040. Premiums continued to rise in 2023, although at a decreasing rate, as inflation has moderated and legal reforms have kicked in.

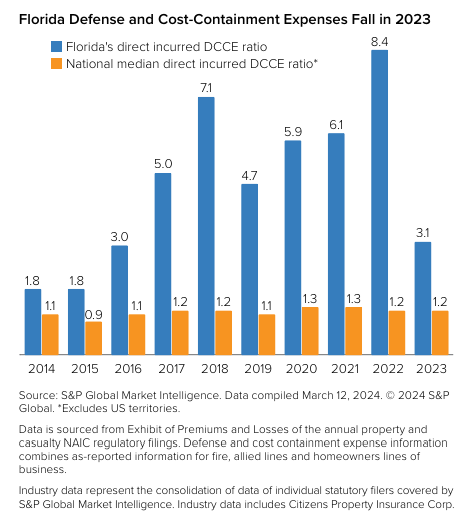

There are early signs that the reforms are beginning to bear fruit. In 2023, Florida’s defense and cost-containment expense (DCCE) ratio – a key measure of the impact of litigation – fell to 3.1, from 8.4 in 2022, according to S&P Global. In dollar terms, 2023 saw $739 million in direct incurred legal defense expenses – a major decline from 2022’s $1.6 billion. For perspective, incurred defense costs in the two largest U.S. insurance markets in 2023 were $401.6 million in California, followed by $284.7 million in Texas. As the chart below shows, Florida’s DCCE ratio – even during its best years – regularly exceeds the nation’s.

As insurers have failed or left the state, Citizens Property Insurance Corp. – the state-run insurer of last resort and currently Florida’s largest residential insurance writer – has swelled with new business and lawsuits. Citizens’ depopulation efforts to move policyholders to private insurers contributed to policy counts falling to 1.23 million by the end of 2023.

It’s important to remember that all premium estimates are based on the best information available at the time and actual results may differ due to changes in market conditions. For example, earlier Triple-I projections that average annual homeowners premiums in Florida would exceed $4,300 in 2022 and $6,000 in 2023 assumed significant rate increases would be needed to restore profitability to the state’s homeowners market. These projections did not assume legislative reform or that Citizens would become the state’s largest homeowners insurance company, with many risks priced below the admitted and excess and surplus markets. Our projections also assumed inflation would continue to grow at rates similar to those prevailing at the time.

In light of the reforms and moderating inflation, we are now reporting lower average annual premiums of $3,040 (2022) and $3,340 (2023). The Florida OIR has reported average premium rate filings are running below 2.0 percent in 2024 year-to-date in the private market. Further, OIR indicated eight domestic carriers have filed for rate decreases and 10 have filed for no increase this year. Additionally, eight property insurers have been approved to enter the Florida market, with more expected this year.

Triple-I will continue to monitor and report on the evolving property insurance market in Florida.