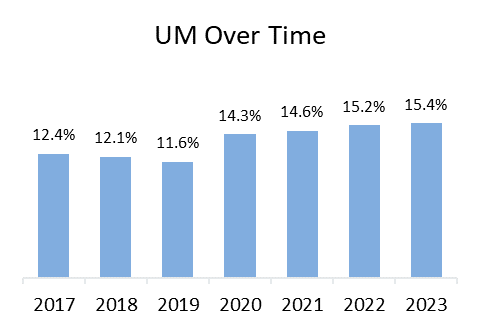

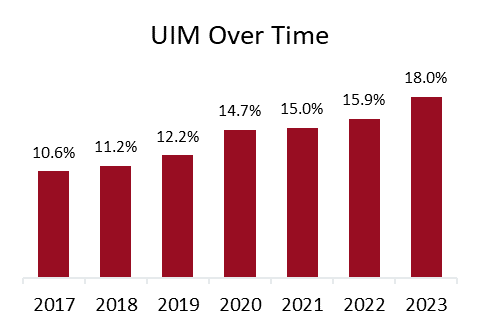

In 2023, despite nearly universal legal requirements to have auto insurance, more than one in seven drivers (15.4 percent) nationally were uninsured, and more than one in six drivers (18.0 percent) were underinsured, according to the new report, Uninsured and Underinsured Motorists: 2017–2023, by the Insurance Research Council (IRC), affiliated with The Institutes. Across the fifty states and the District of Columbia, one in three drivers (33.4 percent) were either uninsured or underinsured in 2023, a 10 percentage point increase in the combined rate since 2017.

Using data submitted by 17 insurers — representing approximately 55 percent of the private passenger auto insurance market countrywide — this latest report estimated the prevalence of uninsured (UM) and underinsured (UIM) by comparing the frequency of UM claims and UIM claims, respectively, to the frequency of bodily injury (BI) claims. Findings included an analysis of trends and contributing factors to variations in UM and UIM rates across states.

The IRC analyzed UM, UIM, and BI liability exposure and claim count data from participating companies for 2017 through 2023. Because of the disruption of the pandemic shutdowns, the changes over time were split into three periods (details outlined in the report).

Key IRC findings include:

- UM rates varied substantially across the nation (50 states and the District of Columbia)

- Nearly every state saw a rise in the UM rate in 2020 with the onset of the pandemic, but the experience from 2020 to 2023 was mixed.

- Every state, except for New York and the District of Columbia, experienced a rise in UIM rate between 2017 and 2023.

- Many states with high UM rates often also have high UIM rates. However, some jurisdictions, such as Nevada and Louisiana, combine below-average UM rates with high UIM rates, while others, such as the District of Columbia, have high UM rates but low UIM rates.

- Several factors, including economic factors, insurance costs, and state insurance laws and regulations, are associated with variations in UM and UIM rates across states.

After the initial shock of the pandemic, the UM rate increased steadily.

Before the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, UM rates were falling in most states. From 2017 to 2019, only 11 jurisdictions saw an increase. UM claim frequency fell slightly in 2020 to 0.11 claims per 100 insured vehicles, but the decline was much smaller than the drop in BI claim frequency. UM claim frequency recovered quickly and, in the years since 2020, has grown faster than BI claim frequency (39 percent compared with 29 percent).

As a result, the UM rate has increased steadily, reaching 15.4 percent in 2023. The range of the UM rates spanned from a low of 5.7 percent in Maine to a high of 28.2 percent in Mississippi. Outliers include eight states with UM rates above 20 percent and 11 states with rates lower than 10 percent.

States with above-average BI claim frequency and UM claim frequency tended to have higher UM rates. Yet, some states with low UM claim frequency rates have a relatively high UM rate. In Michigan, for example, strict no-fault rules limit the number of BI claims, so the ratio of UM-to-BI claim frequencies is high. Lower UM rates tended to occur in states with higher income, lower unemployment rates, lower insurance expenditures, low minimum limits, and a lack of stacking provisions.

UM rates were higher in states that don’t require UIM coverage. In 2023, the UM rate was 14.9 percent in states that do not require UIM insurance, compared with 11.6 percent in states that require it. Where UIM coverage isn’t required by law, UM rates were significantly higher in the years captured in this study, with the rate in 2023 at 18.9 percent in states that don’t require UIM insurance, compared with 13.3 percent in states that require it.

Nearly one in five accidents with injuries involved losses more than the at-fault driver’s coverage limits.

Over the study period, nearly every jurisdiction experienced an increase in its UIM rate. The only exceptions were a small decline (0.9%) in the District of Columbia and a 6.6 percent decline in New York. The largest increase occurred in Colorado, where the UIM rate rose 24.4 percentage points. Other states with above-average increases included Michigan, Kentucky, and Georgia.

UIM claim frequency showed a small increase between 2017 and 2019 before dropping slightly in 2020. In the years since the onset of the pandemic, with the severity of auto injury claims on the rise, UIM claim frequency has increased markedly, reaching 0.17 claims per 100 insured vehicles in 2023. Since 2020, the growth in UIM claim frequency was double the growth in BI frequency. As a result, the UIM rate has increased significantly, rising to 18.0 percent in 2023.

IRC analysis showed that characteristics associated with lower UIM rates included higher income, lower unemployment rates, lower insurance expenditures, high or medium minimum limits, lack of stacking provisions, and use of a limits trigger for UIM coverage rather than a damages trigger. States with high UM rates often also have high UIM rates. Florida, Colorado, and Michigan all rank relatively high for both measures, while Maine, Massachusetts, and Nebraska all rank relatively low.

“The increase in UIM rates points to higher UIM premiums in the future, worsening affordability and potentially increasing the likelihood of more uninsured drivers. This demonstrates the complex interconnectedness of these two coverages as insurers protect consumers from insufficient coverage by at-fault drivers,” said Dale Porfilio, president of the IRC and chief insurance officer at the Insurance Information Institute (Triple-I).

While state laws regarding mandatory requirements for uninsured and underinsured motorists vary, nearly all states have a legislation framework that requires all drivers to have some auto liability insurance to drive a motor vehicle. Drivers in most states are also required to purchase additional protection to provide coverage if the at-fault driver cannot afford to pay for the damage they caused. However, legislators in several states have enacted “no pay, no play” laws, which ban uninsured drivers from suing for noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering. A handful of states have programs to assist lower-income drivers, and drivers can check with their state’s insurance division to see if they are eligible.

To learn more about UM/UIM trends, read the IRC report, Uninsured and Underinsured Motorists: 2017–2023, and check out the Triple-I Backgrounder on Compulsory Auto/Uninsured Motorists.