California is not the only U.S. state struggling with insurance availability and affordability, but — as described in a new Triple-I Issues Brief — its problems are exacerbated by a three-decades-old legislative measure that severely constrains insurers’ ability to profitably insure property in the state.

Instead of letting insurers use the most current data and advanced modeling technologies to inform pricing, Proposition 103 requires them to price coverage based on historical data alone. It also bars insurers from incorporating the cost of reinsurance into their prices.

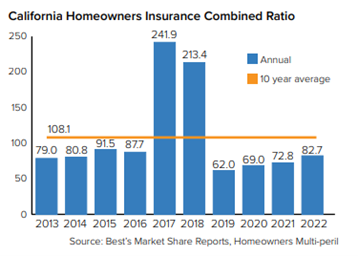

Insurers’ underwriting profitability is measured using a “combined ratio” that represents the difference between claims and expenses insurers pay and the premiums they collect. A ratio below 100 represents an underwriting profit, and one above 100 represents a loss.

As the chart shows, insurers have earned healthy underwriting profits on their homeowners business in all but two of the 10 years between 2013 and 2022. However, the claims and expenses paid in 2017 and 2018 – due largely to wildfire-related losses – were so extreme that the average combined ratio for the period was 108.1.

Underwriting profitability matters because that is where the money comes from to maintain “policyholder surplus” – the funds insurers set aside to ensure that they can pay future claims. Integral to maintaining policyholder surplus is risk-based pricing, which means aligning underwriting and pricing with the cost of the risk being covered. Insurers hire teams of actuaries and data scientists to make sure pricing is tightly aligned with risk, and state regulators and lawmakers closely scrutinize insurers to make sure pricing is fair to policyholders.

To accurately underwrite and price coverage, insurers must be able to set premium rates prospectively. As shown above, one or two years that include major catastrophes can wipe out several years of underwriting profits – thereby contributing to the depletion of policyholder surplus if rates are not raised.

California is a large and potentially profitable market in which insurers want to do business, but current loss trends and the constraints of Proposition 103 have caused several to reassess their appetite for writing coverage in the state. Wildfire losses, combined with events like early 2023’s anomalous rains and, more recently, Hurricane Hilary, increase the urgency for California to continue investing in risk reduction and resilience. The state also needs to update its regulatory regime to remove impediments to underwriting.

An effort in the state legislature to rectify some of the issues making California less attractive to insurers failed in September 2023. With fewer private insurance options available, more Californians are resorting to the state’s FAIR plan, which offers less coverage for a higher premium.

Want to know more about the risk crisis and how insurers are working to address it? Check out Triple-I’s upcoming Town Hall, “Attacking the Risk Crisis,” which will be held Nov. 30 in Washington, D.C.